Metabolic engineers have a problem: cells are selfish. The scientists want to use microbes to produce chemical compounds for industrial applications. The microbes prefer to concentrate on their own growth.

Kristala L. Jones Prather ’94 has devised a tool that satisfies both conflicting objectives. Her metabolite valve acts like a train switch: it senses when a cell culture has reproduced enough to sustain itself and then redirects metabolic flux—the movement of molecules in a pathway—down the track that synthesizes the desired compound. The results: greater yield of the product and sufficient cell growth to keep the culture healthy and productive.

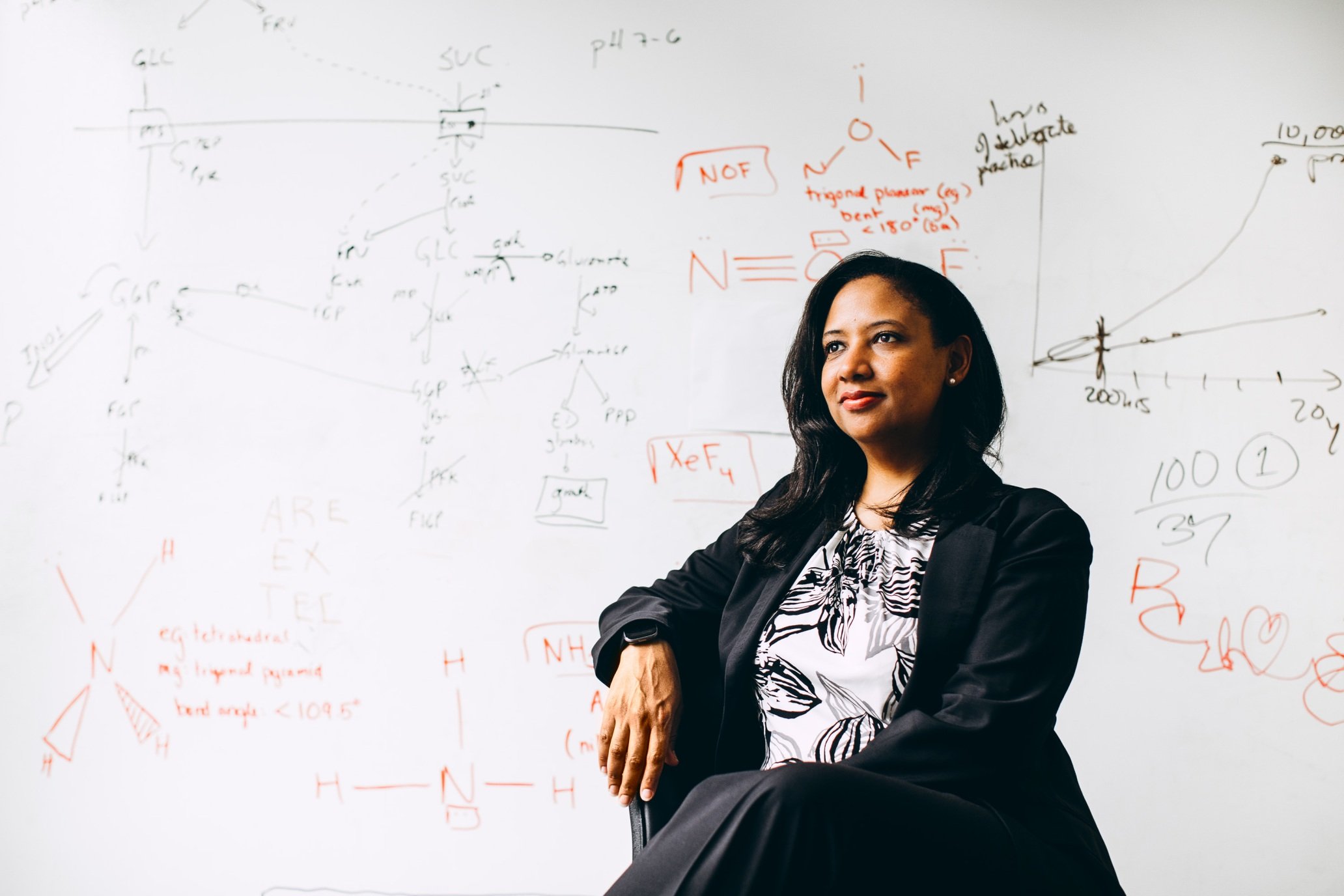

Professor Kristala Jones Prather ’94 has made it practical to turn microbes into efficient producers of desired chemicals. She’s also working to reduce our dependence on petroleum.

William E. Bentley, a professor of bioengineering at the University of Maryland, has been following Prather’s work for more than two decades. He calls the valves “a new principle in engineering” that he anticipates will be highly valued in the research community. Their ability to eliminate bottlenecks can prove so essential to those attempting to synthesize a particular molecule in useful quantities that “in many cases it might decide whether it is a successful endeavor or not,” says Bentley.

Prather, MIT’s Arthur D. Little Professor of Chemical Engineering, labors in the intersecting fields of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering: a place where science, rather than art, imitates life. The valves play a major role in her larger goal of programming microbes—chiefly E. coli—to produce chemicals that can be used in a wide range of fields, including energy and medicine. She does that by observing what nature can do. Then she hypothesizes what it should be able to do with an assist from strategically inserted DNA.

“We are increasing the synthetic capacity of biological systems,” says Prather, who made MIT Technology Review’s TR35 list in 2007. “We need to push beyond what biology can naturally do and start getting it to make compounds that it doesn’t normally make.”

Prather describes her work as creating a new kind of chemical factory inside microbial cells—one that makes ultra-pure compounds efficiently at scale. Coaxing microbes into producing desired compounds is safer and more environmentally friendly than relying on traditional chemical synthesis, which typically involves high temperatures, high pressures, and complicated instrumentation—and, often, toxic by-products. She didn’t originate the idea of turning microbes into chemical factories, but her lab is known for developing tools and fine-tuning processes that make it efficient and practical.

That’s the approach she has taken with glucaric acid, which has multiple commercial applications, some of them green. Water treatment plants, for example, have long relied on phosphates to prevent corrosion in pipes and to bind with metals like lead and copper so they don’t leach into the water supply. But phosphates also feed algae blooms in lakes and oceans. Glucaric acid does the same work as phosphates without feeding those toxic blooms.

...